MEDICARE COMPLIANCE

Welcome to Synergy’s blog page dedicated to the topic of Medicare compliance. Our team of Medicare experts share their InSights and knowledge on the latest developments and best practices for law firms to stay compliant with the MSP. Stay up-to-date with the latest trends and strategies to ensure that you have the information you need to navigate the complex world of Medicare compliance. Our blogs provide practical tips and advice for ensuring that your clients receive the medical care they need while complying with Medicare’s requirements. Let our experts guide you through the intricacies of Medicare compliance and help you stay on top of the latest developments in this rapidly-evolving field.

Jason D. Lazarus, J.D., LL.M., CSSC, MSCC

On March 18, 2019, the United States Attorney for the District of Maryland announced that the law firm of Meyers, Rodbell & Rosenbaum, P.A., has agreed to pay the United States $250,000 to settle claims that it did not reimburse Medicare for payments made on behalf of a firm client. As part of the settlement, the firm “also agreed to (1) designate a person at the firm responsible for paying Medicare secondary payer debts; (2) train the designated employee to ensure that the firm pays these debts on a timely basis; and (3) review any outstanding debts with the designated employee at least every six months to ensure compliance.”

This is the second such settlement in the last year. In June 2018, a similar settlement was announced by the U.S. Department of Justice Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. To read more about this prior settlement, click HERE. Both of these settlements should remind attorneys of “their obligation to reimburse Medicare for conditional payments after receiving [a] settlement or judgment proceeds for their clients [as well as] not to disburse settlement proceeds until receipt of a final demand from Medicare to pay the outstanding debt.”

In today’s complicated regulatory landscape, a comprehensive plan for Medicare compliance has become vitally important to personal injury practices. Lawyers assisting Medicare beneficiaries are personally exposed to damages and malpractice risks daily when they handle or resolve cases for Medicare beneficiaries. The list of things to be concerned about is growing daily. The list includes things such as:

- Not knowing what medical information/ICD codes are being reported by defendant insurers complying with Mandatory Insurer Reporting law (MIR) created by MMSEA.

- Agreeing to onerous “Medicare Compliance” language—that may be inapplicable or inaccurate –which binds the personal injury victim.

- Failing to report and resolve conditional payment obligations leading to personal liability.

- Not using processes to obtain money back from Medicare using the compromise and waiver process.

- Failure to identify a lien, such as those asserted by Medicare Part C lien holders thereby exposing the personal injury lawyer and the firm to double damages.

- Inadequate education of clients about Medicare compliance when it comes to ‘futures’ and the risks of denial of future injury-related care.

What do you do? The answer is to develop a process to identify those who are Medicare beneficiaries in your practice and make sure that a process is put into place to deal with the myriad of issues that can arise. Given the liability a law firm faces for failing to be compliant, outsourcing this function to experts like those at Synergy helps mitigate the firm’s risk. Synergy’s Total Medicare Compliance program allows a law firm to address issues like Medicare Conditional Payment obligations, Medicare Advantage liens as well as Medicare Set Aside concerns by turning to us.

All lawyers assisting those on Medicare must be in the know when it comes to dealing with Medicare conditional payments as well as Part C/MAO liens. Medicare beneficiaries must understand the risk of losing their Medicare coverage should they decide to set-aside nothing from their personal injury settlement for future Medicare covered expenses related to the injury. Ultimately, it is about educating the client to make sure they can make an informed decision relative to these issues. Beyond education of the client, the most critical issue becomes how to properly document your file about what was done and why. This part is where the experts come into play. For most practitioners, it is nearly impossible to know all the nuances and issues that arise with the Medicare Secondary Payer Act. From identifying liens, resolving conditional payments, deciding to set money aside, the creation of the allocation to the release language and the funding/administration of a set aside, there are issues that can be daunting for even the most well-informed personal injury practitioner. Without proper consultation and guidance, mistakes can lead to unhappy clients or worse yet a legal malpractice claim.

For more information about our Medicare Compliance services, click here.

Medicare Advantage Private Cause of Action is Now Sweeping the Country

Courts across the country continue to rule that Medicare Advantage Plans (MAP or MAO) are enforceable and shall be entitled to double damages if not repaid in third party liability situations. The trial bar has been aware of this significant exposure since 2016 when Humana Insurance Company v. Paris Blank LLP et al., No. 3:2016cv00079 – Document 23 (E.D. Va. 2016) confirmed that attorneys are personally liable to repay Medicare Advantage plans. (See previous Synergy Blog Post). Adding to the concern is Western Heritage’s ruling which stated that the amount due “shall” be double the amount of the Medicare Advantage plan’s Final Demand (Humana v. Western Heritage Insurance Co., No. 15-11436 (11th Cir. 2016) (See previous Synergy Blog Post)). Two recent cases continue the reasoning that Medicare Advantage Plans, via the Medicare Secondary Payer Act, have a private cause of action and are entitled to double damages when a “primary plan” fails to reimburse them for conditional payments made on behalf of a beneficiary.

The first is Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Guerreras, et al. filed in the US District Court for the District of Connecticut. In this case, Aetna, who was the Medicare Advantage Plan, filed an action against Nellina Guerrera, her attorneys and the defendant in the personal injury action. Guerrera and her attorneys were dismissed. However, the case is moving forward against the defendant. The private cause of action provision, entitling Aetna to double damages, was not dismissed against Big Y, the defendant, as they were found to be the primary plan or payer as defined by the MSP law. Big Y’s duty was to be sure that Aetna was reimbursed and this was not guaranteed or accomplished by making payment to the insured and their attorney.

The second case is Humana, Inc, United Healthcare Services, Inc. and Aetna, Inc. v. Shrader Sc Associates LLP, out of the US District Court for the Southern District of Texas. In this case, Shrader Associates LLP (a Plaintiff’s law firm representing asbestos trusts) argued that the trusts were not primary plans under the MSP “primary plan” definition. The court disagreed in this opinion, holding that the MSP permits a MAP to sue a primary plan that fails to reimburse it for primary payments.

Unlike the Connecticut case, which held that attorneys are not personally liable, the Texas court found, as has every other court who has dealt with this issue, that attorneys are “primary plans” and are personally liable. In Shrader, the court found that attorneys are expressly listed in the regulations as a “primary plan.”

42 C.F.R. §411.24(g):

“CMS has a right of action to recover its payments from any entity, including a beneficiary, provider, supplier, physician, attorney, State agency or private insurer that has received a primary payment.”

And

42 C.F.R. § 411.24(i)(1):

“If a beneficiary or other party fails to reimburse Medicare within 60 days of receiving primary payment, the primary plan ‘must reimburse Medicare even though it has already reimbursed the beneficiary or other party.”

42 U.S.C. § 1395y(b)(3)(A)

There is established a private cause of action for damages (which shall be in an amount double the amount otherwise provided) in the case of a primary plan which fails to provide for [ ] payment … or reimbursement.

Trial Attorneys Beware!

If a trial attorney reports a case to Medicare and the plaintiff is actually on a Medicare Advantage Plan, neither CMS nor BCRC inform the trial attorney. Unless the plaintiff has informed the trial attorney of the existence of a Medicare Advantage Plan, there is no way for the attorney to know. There is no “portal” to check, or central repository of information from which a trial attorney could obtain some level of certainty that any potential repayment obligation is satisfied. Medicare Advantage plans are not required to follow any of the reporting or disclosure obligations that exist for traditional fee-for-service Medicare (A&B) plans. Humana and other Medicare Advantage plans continue to benefit from this lack of transparency to avoid disclosure and to make the private cause of action a profit center funded by the trial bar.

The burden is on the trial attorney to discover and satisfy these Medicare Advantage repayment obligations or potentially be forced to pay double themselves. A few best practices:

- Get all insurance cards from your client or their personal representative – Clients on Medicare Advantage plans often refer to their coverage as Medicare.

- Confirm effective dates of coverage – Clients can switch back and forth from Medicare A&B to an MAO and back each year.

- Potentially a repayment obligation to both CMS and an MAO may exist in the same case for the same accident, so you must check for both.

- If you are expecting a large conditional payment amount from CMS and it is small or zero this should be a red flag that potentially an MAO is paying.

- Review billing statements from hospitals and providers to determine if an MAO is making payment.

- Consult an expert.

Another likely result of this case is that the trial attorney should now expect the same treatment of Medicare Advantage claims by defense counsel as is now the case with Medicare A&B. Defense counsel may demand written confirmation that any purported Medicare Advantage lien has been satisfied, and may be reluctant to disburse funds to the plaintiff with only the expectation that the plaintiff will satisfy this obligation.

Synergy will continue to actively protect injury victims and the attorneys who represent them. If you are having an issue with Medicare or Medicare Advantage plans give us a call and speak to an expert (877) 242-0022.

Janice Vincent

Senior Medicare Lien Resolution Specialist

New Medicare Portal Goes Live January 2016

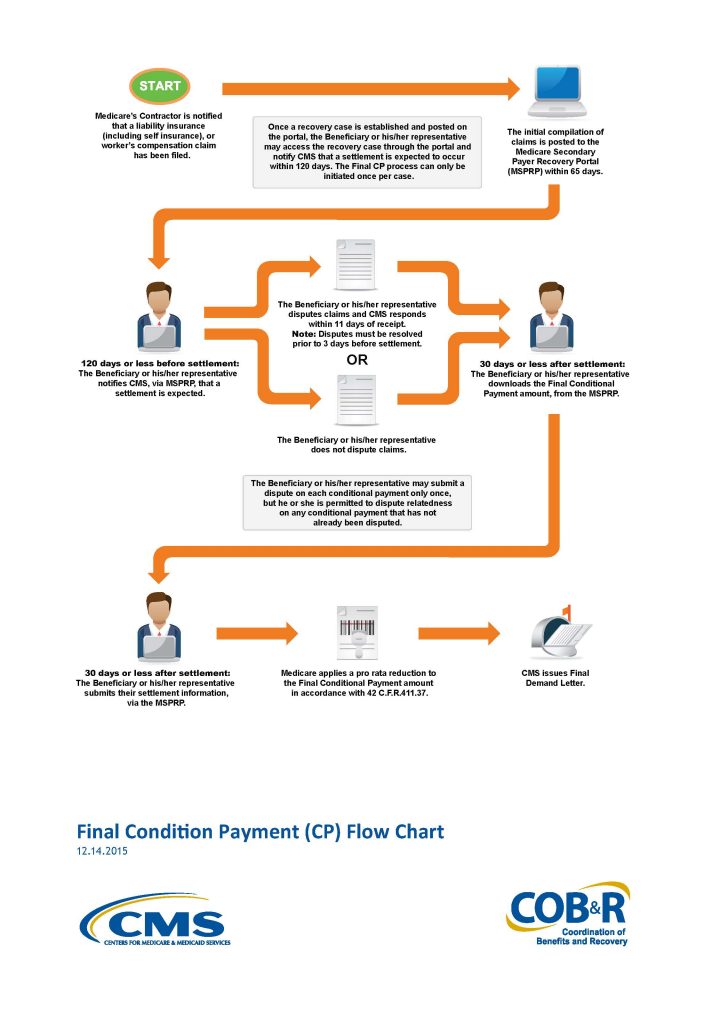

On November 9th 2015, The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the much anticipated, and long overdue, start date for the new Medicare Secondary Payer Recovery Portal (MSPRP). The new MSPRP will begin functioning on January 1, 2016. The current MSP Web portal permits authorized users to register through the Web portal in order to access MSP conditional payment amounts electronically and update certain case-specific information online.

CMS is adding functionality to the existing MSP Web portal that will permit users to notify them when the specified case is approaching settlement, download or otherwise obtain time and date stamped Final Conditional Payment Summary forms and amounts before reaching settlement. Additionally, the new MSP Web portal will ensure that relatedness disputes and any other discrepancies are addressed within eleven business days of receipt of dispute documentation.

The process is rather straight forward and will address many of the issues that have plagued the plaintiff’s bar in attempting to settle a personal injury action without any certainty of the repayment amount due Medicare. The process will begin when the beneficiary, their attorney or other representative (such as Synergy) provides the required notice of a pending liability insurance settlement to the appropriate Medicare contractor at least one hundred eighty five days before the anticipated date of settlement.

If the beneficiary, their attorney or other representative (Synergy), believes that claims included in the most up-to-date Conditional Payment Summary form are unrelated to the pending liability insurance “settlement”, they may address discrepancies through a dispute process available through the MSP Web portal. This dispute may be made once and only once. Following the dispute CMS has only eleven business days to resolve the dispute.

After disputes have been fully resolved, and a final claims refresh has been executed on the MSP Web portal, then a time and date stamped Final Conditional Payment Summary may be downloaded through the MSP Web portal. This form will constitute the Final Conditional Payment amount if settlement is reached within 3 days of the date on the Conditional Payment Summary.

The plaintiff attorney will complete the process by providing, within thirty days, the settlement information to CMS via the MSP Web portal. This information will include, but is not limited to: the date of “settlement”, the total “settlement” amount, the attorney fee amount or percentage, and additional costs borne by the beneficiary to obtain his or her “settlement”. If this information is not provided within thirty days, the Final Conditional Payment amount obtained through the Web portal will expire.

In Humana Medical Plan, Inc. v. Western Heritage Insurance Co., No. 12-20123, 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 31875, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida granted Humana’s Motion for Summary Judgment and held that Humana’s right to reimbursement for the conditional payments it made on behalf of plan beneficiary under a Medicare Advantage Plan was enforceable. Consequently, Humana was entitled to double damages pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1395y(b)(3)(A).

In resolving the underlying personal injury action that gave rise to this case, the plaintiff confirmed there were no outstanding Medicare liens against the settlement proceeds. As evidence the plaintiff presented a letter from The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (”CMS”) dated December 3, 2009 which confirmed CMS had no record of processing Medicare claims on behalf of the plaintiff.

Eventually Western Heritage, the third party carrier, learned of Human’s Medicare Advantage lien and attempted to include Humana as a payee on the settlement draft. The state court judge ordered full payment to the plaintiff without including any lien holder on the settlement check. The judge simultaneously ordered plaintiff’s counsel to hold sufficient funds in a trust account to be used to resolve all medical liens.

While Humana and the plaintiff remained in ongoing litigation, Humana filed this action against Western Heritage seeking double damages pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1395y(b)(3)(A).

The Medicare Secondary Payer Act (MSP) provides for a private cause of action when a primary plan fails to reimburse a secondary plan for conditional payments it has made.

“there is established a private cause of action for damages (which shall be in an amount double the amount otherwise provided) in the case of a primary plan which fails to provide for primary payment (or appropriate reimbursement) in accordance with paragraphs (1) and (2)(A).”

42 U.S.C. § 1395y(b)(3)(A).

42 C.F.R. §422.108(f) extends the private cause of action to Medicare Advantage Plans (Medicare Advantage Organizations “MAO”s).

“MAOs will exercise the same rights to recover from a primary plan, entity, or individual that the Secretary exercises under the MSP regulations in subparts B through D of part 411 of this chapter.”

Additionally, CMS directors have issued memorandum asserting that:

“notwithstanding recent court decisions, CMS maintains that the existing MSP regulations are legally valid and an integral part of Medicare Part C and D programs.”

CMS, HHS Memorandum: Medicare Secondary Payment Subrogation Rights (Dec. 5, 2011).

While the Eleventh Circuit has not yet addressed the issue of whether a Medicare Advantage Organization, such as Humana, may bring a private cause of action against a primary plan under the secondary provision of the Act, the Third Circuit has addressed the issue and held that it can. In Avandia II the Third Circuit reasoned that the Medicare statute should be read broadly and that the language of the Medicare Advantage Organization statute (42 U.S.C. §1395w-22(a)(4)) cross references the Medicare Secondary Payer Act’s (“MSP”) language (42 U.S.C. § 1395y(b)(2)(A)) which allows these plans to utilize the enforcement provision of the MSP (42 U.S.C. 1395y(b)(3)(A)). The Third Circuit added to their opinion that the MAO plans are able to use the MSP. To deny them this ability, would put them at a competitive disadvantage, and moreover that the federal agency had enacted reasonable regulations in 42 C.F.R. § 422.108. This regulation is relied on by the MAO plans in their recovery actions as it states that the MAO plans have the same recovery rights as traditional Parts A & B

Unlike the Third Circuit the Ninth Circuit in Parra v. Pacificare of Arizona, 2013 U.S. App. LEXIS 7861 was not persuaded that the cross referencing of the MAO Statute (42 U.S.C. §1395w-22(a)(4) ) and the MSP (42 U.S.C. §1395y(b)(2)) created a federal cause of action. The Ninth reasoned that this cross-reference simply explains when MAO coverage is secondary to a primary plan, but does not create a federal cause of action in favor of a MAO. Here the Court found that “[l]anguage in a regulation may invoke private right of action that Congress through statutory text created, but it may not create a right that Congress has not”. They elaborated by stating in clear terms that, “It is relevant laws passed by Congress, and not rules or regulations passed by an administrative agency, that determine whether an implied cause of action exists”.

Western Heritage argues that this Court should follow Parra and “interpret the Medicare Act as not providing a private right of action in favor of MAOs such as Humana.” However, as predicted in my last post on this topic the holding in Parra is too narrow to be of any assistance and the Court here finds the facts of Parra distinguishable. The Court found the Third’s Circuit’s analysis regarding the ability of an MAO to bring a private cause of action under the MSP Act to be persuasive.

Pursuant to the MSP Act’s private cause of action, the Court found that Humana has a right to recover from Western Heritage the benefits it paid and is statutorily entitled to recover double damages. Additionally, “if Medicare is not reimbursed as required by paragraph (h), the primary payer must reimburse Medicare even though it has already reimbursed the beneficiary or other party.” 42 C.F.R. § 411.24(i)(1). Therefore, the Court concludes that after Western Heritage became aware of payments by the Humana Medicare Advantage Plan it had an obligation to independently reimburse Humana. Because it didn’t, the Court rules that as a matter of law, Humana is entitled to maintain a private cause of action for double damages pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1395y(b)(3)(A) and is therefore entitled to $38,310.82 in damages.

The trial attorney should now expect the same treatment of Medicare Advantage claims by defense counsel as is now the case with Medicare A & B. Defense counsel will likely demand written confirmation that any purported Medicare Advantage has been satisfied, and may be reluctant to disburse funds to the plaintiff based solely on the expectation that the plaintiff will satisfy this obligation. As a matter of practice it may be more expedient to have defense issue separate settlement drafts to the plaintiff and the MAO rather than a single check with two (2) payees.

What is the statute of limitations for Medicare to institute an action for repayment of conditional payments used to be a question with more than one answer. In the past the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) had argued that the six (6) year limitation period contained in the Federal Debt Collection Act for claims arising out of contract was the correct standard for the plaintiff attorney. That statute provides:

“every action for money damages brought by the United States or an officer or agency thereof which is founded upon any contract express or implied in law or fact, shall be barred unless the complaint is filed within six years after the right of action accrues…”

28 USC § 2415(a)

The plaintiff’s bar and Medicare enrollees argued that the shorter three (3) year statute of limitations was the correct standard for claims arising out of tort. That statute provides:

“every action for money damages brought by the United States or an officer or agency thereof which is founded upon a tort shall be barred unless the complaint is filed within three years after the right of action first accrues…”

28 U.S.C. § 2415(b).

When President Obama signed the Strengthening Medicare and Repaying Taxpayers Act (“SMART”) on January 10, 2013 he answered this question in favor of Medicare beneficiaries. Additionally, unlike some of the other components of the “SMART” Act this section is self-enacting and does not need rule promulgation or post a proposed rulemaking in the Federal Register for this to be effective. By operation of statute this new time limit became effective six (6) months after signing. Therefore, all cases that settle after July 10, 2013 will be controlled by the three (3) year statute of limitations. The “SMART” Act reads in pertinent part:

“(a) In General.–Section 1862(b)(2)(B)(iii) of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. 1395y(b)(2)(B)(iii)) is amended by adding at the end the following new sentence: `An action may not be brought by the United States under this clause with respect to payment owed unless the complaint is filed not later than 3 years after the date of the receipt of notice of a settlement, judgment, award, or other payment made…’”

Pub. L. No. 112-242, § 205(a) (2013)

In the recent case U.S. v. Stricker, Lexis 15204 (11th Cir. July 26, 2013) the court provides an excellent analysis of the above competing statutes of limitation and confirms that the “SMART” Act has resolved the controversy for settlements after July 10, 2013. The Stricker Court discussed the need and purpose of federal statute of limitations:

The purpose of a statute of limitations, such as 28 U.S.C. § 2415, “is to require the prompt presentation of claims.” Coppage v. U.S. Postal Serv., 281 F.3d 1200, 1206 (11th Cir. 2002) (internal quotation marks and citation omitted). Originally, there was no statute of limitations for lawsuits filed by the government. Congress, however, passed § 2415-a statute of limitations that applies to the United States [*14] -“to promote diligence by the government in bringing claims to trial and also to make the position of the government more nearly equal to that of a private litigant.” United States v. Kass, 740 F.2d 1493, 1496 (11th Cir. 1984).

The new three (3) year statute of limitations under the “SMART” Act addresses that need and the complaint of so many Medicare beneficiaries who wonder if there is ever an end to CMS’s demand for repayment. It is now incumbent on the plaintiff’s attorney to report settlements to CMS (via their contractor MSPRC) so that the three (3) year timer starts running as soon as possible.

For help with Medicare Conditional payment resolution, turn to Synergy. Synergy offers a unique post payment of final demand service where we attempt to secure a refund back from Medicare via the compromise/waiver process. There is a small administrative fee at the outset and then Synergy only gets paid if there is a refund on a percentage of savings basis. To learn more about Synergy’s lien resolution services, visit www.synergylienres.com

By Director of Lien Resolution

An Administrative Services Agreement between a Plan Administrator and a Claims Administrator may fall within the purview of a document request under ERISA 29 U.S.C. § 1024(b)(4), with non-compliance subject to the penalty assessment authorized under ERISA 29 U.S.C. § 1132(c). As Synergy has long advocated, one of the keys to properly defending against an asserted subrogation or reimbursement claim from an ERISA plan is making requests to the plan administrator. ERISA places certain responsibilities upon the Plan Administrator to assist with the proper management of ERISA qualified employee welfare-benefit plans and to promote communication with the plan beneficiaries.

One of the major responsibilities of the plan administrator, in so far as dealing with providing information to beneficiaries, is contained in 29 U.S.C. 1024(b)(4). This section of the statute deals with requests for information made upon the plan administrator:

29 U.S.C. 1024(b)(4)– The administrator shall, upon written request of any participant or beneficiary, furnish a copy of the latest updated summary plan description, and the latest annual report, any terminal report, the bargaining agreement, trust agreement, contract, or other instruments under which the plan is established or operated.

In Grant v. Eaton, S.D.Miss, Civil Action No. 3:10CV164TSL-FKB, decided 2/6/13, there was an allegation that the Administrative Services Agreement between the third party claims administrator and the plan administrator contained a provision that purports to grant discretion as well as authority from the plan administrator to the claims administrator. Due to this allegation of the transfer of certain rights from the Plan to the Claims Administrator, the court found that the Administrative Services Agreement was not excluded from the 29 U.S.C. 1024(b)(4) requests and the failure to provide the contract would subject the plan to penalties under 29 U.S.C. § 1132(c)(1)(B).

The court further reasoned that the Administrative Services Agreement contained information on “who are the persons to whom the management … of his plan … have been entrusted.” Hughes Salaried Retirees Action Comm., 72 F.3d 686, 690 (9th Cir. 1995). As a result, the Court found that the Administrative Services Agreement was subject to the ERISA disclosure requirements as it is a document “that restrict[s] or govern[s] a plan’s operation.” Shaver v. Operating Eng’rs Local 428 Pension Trust Fund, 332 F.3d 1198, 1202 (9th Cir. 2003).

The Southern District of Mississippi relied upon the rationale of other courts who had evaluated whether or not a 29 U.S.C. 1024(b)(4) request included Administrative Services Agreements. In Michael v. American International Group, Inc., No. 4:05CV02400 ERW, 2008 WL 4279582 (E.D. Mo. 2008), the court wrote at length on the issue, stating, in pertinent part,

“The proper inquiry for the Court to determine whether the contract at issue should have been disclosed is to consider whether the administrative services agreement “allow[s] ‘the individual participant [to] know … exactly where he stands with respect to the plan-what benefits he may be entitled to, what circumstances may preclude him from obtaining benefits, what procedures he must follow to obtain benefits, and who are the persons to whom the management and investment of his plan funds have been entrusted.”

(See also, Hughes Salaried Retirees Action Comm. v. Administrator of the Hughes Non-Bargaining Retirement Plan, 72 F.3d 686, 690 (9th Cir. 1995)).

The court also looked to the Eleventh Circuit and noted that the Eleventh Circuit has found that the Administrative Services Agreement may be subject to disclosure under ERISA not just as “other instruments under which the plan is established or operated” but as a “contract” pursuant to 29 U.S.C. § 1024(b)(4). Heffner v. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama, Inc., 443 F.3d 1330, 1343 (11th Cir. 2006). The Eleventh Circuit succinctly stated that “[a] contract between a group and an insurer such as Blue Cross is specifically listed as an ERISA document which may control a plan’s operation.”

The court also recognized Fisher v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 895 F.2d 1073, 1077 (5th Cir. 1990) which noted that the Plan, by its own terms, contemplated delegation of the Plan Administrator’s responsibilities to a third party administrator “arguably incorporat[ed] the Administrative Services Agreement … as a further delineation of how the Plan would in fact operate”. Which meant disclosure of the Administrative Services Agreement was required under a 29 U.S.C. 1024(b)(4) request.

Though there is case law which stands for the opposite conclusion reached by the Southern District of Mississippi, the distinction seems to be one of degree. If the Administrative Services Agreement transfers any authority or discretion, or there are allegations that it does, from the Plan Administrator to another party then under the rationale expressed by the courts above that agreement needs to be provided in response to the beneficiary’s 29 U.S.C. 1024(b)(4) request. Similar to the requirement created by Cigna v. Amara, 131 S.Ct. 1866 which necessitates a comparison between the Summary Plan Description and the Master Plan Document, there is need to review the Administrative Services Agreement to determine if a transfer of authority or discretion has taken place. Under the cases cited, above failure of the Plan Administrator to provide the Administrative Services Agreement so that this review can be conducted could subject the plan to penalties under 29U.S.C. § 1132(c)(1)(b) & 29 CFR § 2575.502c-1.

Forcing a Plan Administrator to fully comply with its obligations under 29 U.S.C. 1024(b)(4) is one of the few ways to exert pressure on a self-funded ERISA plan who is attempting to enforce purported recovery rights. Understanding that neither the Plan Administrator, nor the Claims Administrator, wants to provide their Administrative Services Agreement can be used as a negotiation tool by the wise plaintiff’s attorney to reduce repayment. Get the documents your client is owed, or demand a discount from the Plan or recovery vendor.

Synergy can help with reduction or possibly elimination of ERISA liens. Contact us today to see how we can help you.

An Administrative Services Agreement between a Plan Administrator and a Claims Administrator may fall within the purview of a document request under ERISA 29 U.S.C. § 1024(b)(4), with non-compliance subject to the penalty assessment authorized under ERISA 29 U.S.C. § 1132(c). As Synergy has long advocated, one of the keys to properly defending against an asserted subrogation or reimbursement claim from an ERISA plan is making requests to the plan administrator.

BLOGS

READY TO SCHEDULE A CONSULTATION?

The Synergy team will work diligently to ensure your case gets the attention it deserves. Contact one of our legal experts and get a professional review of your case today.